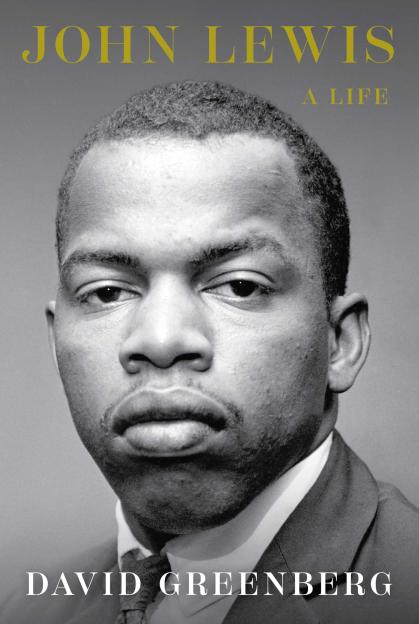

In John Lewis: A Life, Rutgers Professor Pens Portrait of Political Truth, Courage and Compromise

Award-winning author David Greenberg says his new book about the civil rights leader offers hope for uniting a divided nation

To David Greenberg, a professor of history and journalism and media studies at Rutgers University–New Brunswick, one word defines the current atmosphere in Washington, D.C.: divisive.

Two words offer an alternative: John Lewis.

On Oct. 8, after more than five years of research and writing, Greenberg’s latest work, John Lewis: A Life, hits the shelves, a 696-page study of the civil rights icon. Published by Simon & Schuster, the book paints an intimate portrait of a man who demonstrated that leadership fueled by dignity, respect, courage and honesty always can prevail over hostility and hate.

“Lewis took on a luster in the final years of his life,” said Greenberg, a longtime political observer. “Lewis seemed to embody the best of our political traditions.”

John Lewis: A Life traces Lewis’s path from the beating he received on “Bloody Sunday” in Selma, Ala., through his rise in local politics to nearly four decades on Capitol Hill. Drawing on rare archival material and interviews with Lewis and 275 others – including former presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton – the authoritative biography peels back the curtain on a man his colleagues called the “conscience of the Congress.”

“There’s this video footage of John Lewis in his hospital bed, right after the Selma beating, talking to reporters, during which he's talking about nonviolence,” Greenberg said. “The courage, the conviction of holding to these principles, these noble principles of nonviolence that Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. had articulated, is extraordinary. He never relinquished that.”

For Greenberg, readying himself to take on a project of such magnitude required a lifetime of preparation.

While Greenberg teaches journalism at Rutgers, he never worked as a beat reporter – chasing police or attending public hearings. But he did have high-level journalism experience. One of his first jobs in the business was as an intern at the New Republic. That led to a three-year stint as a researcher for Bob Woodward, the famed Washington Post journalist, an experience that eventually brought him back to the New Republic, where, at 26 years old, he was named the magazine’s acting editor.

Then, with a bright journalism career ahead of him, Greenberg left it all behind, trading the reporter’s notepad for the ivory tower in pursuit of a history degree at Columbia University.

“Being handed the reins at the New Republic, for such a young journalist, was a heady experience,” Greenberg said. “People were like, ‘Why did you throw away this promising journalism career to go to graduate school in history?’”

Several reasons, it turns out. For one, his father was a philosophy professor at Brandeis University, and the lifestyle of an academic appealed to Greenberg. He also reveled in intellectual pursuits and felt that journalism only scratched the surface of his interests.

“While I admired many of the Washington journalists I was surrounded by, there could be a superficiality to the profession,” he said. “If I didn’t go on to be an academic, I at least wanted to know the literature that historians read, the kinds of questions they asked, the kinds of methods they used.”

Greenberg received his doctorate in history in 2001 and was immediately faced with a quandary: “Do I go back to journalism, or do I pursue a history position?”

He opted for the latter and, in a fluke, found both.

“The first good tenure track job I got offered was at Rutgers, but it wasn’t in the history department. It was in the journalism department. Then, within a few years, I had a split appointment with the history department.”

Greenberg joined the Rutgers faculty in 2004. His first book, Nixon’s Shadow: The History of an Image, was published a year earlier; it explores the development of President Richard Nixon’s public persona. His second book, a biography of President Calvin Coolidge came out in 2006. A decade later, his third book, Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency, netted a number of awards, including the 2017 Goldsmith Book Prize from Harvard.

John Lewis: A Life may be his most ambitious book yet.

“It was a labor of love,” Greenberg said. “I just felt things kind of humming and coming together as I worked on it. I don't know whether a younger, less experienced book writer, a less experienced version of me, would have managed it.”

Although they spoke over the phone several times, Greenberg met with Lewis only once, a brief conversation in early 2019 – about a year and a half before the congressman’s death.

Lewis had just tossed the ceremonial Super Bowl coin and was about to head to Los Angeles to present the film Green Book at the Oscars.

“He fit me into a small 45-minute window,” the author recalled. “My intent was simple – to ask his blessing for the book. As soon as I asked him, he's like, ‘Yeah, I'm happy to cooperate.’ It was as simple as that.”

Lewis’s support to the project opened the door for other people to participate, many of whom spent hours speaking with Greenberg and providing insights, stories and documents. One source, an assistant and friend named Archie Allen, had been collecting material on Lewis since the late 1960s – “17 binders of gold,” Greenberg said – that included the late congressman’s birth certificate, a report card and even his college acceptance letter.

Other periods of Lewis’s life were less well chronicled, particularly his tenure in Washington, D.C. For those years, Greenberg drew on what he’d learned from Woodward, diligently reporting and speaking with as many people as he could, and “not being afraid to interview someone a second time, a third time, even a fourth time.”

The result is the most definitive story of one of America’s most impactful evangelists of racial equality.

“I came to see John Lewis not just as a civil rights leader, but also as a very political figure – and not in a bad way,” said Greenberg.

Unlike so many politicians today who are empowered by bitterness and hostility, Lewis “was a man of conviction who knew when to compromise,” Greenberg added.