Two Mason Gross Professors Are Featured in Zimmerli’s Abstract Art Exhibit

“Crossing Borders: Geometric Abstraction 1960,” which includes works by painters Julie Langsam and Stephen Westfall, opens Sept. 11 and ends July 31

The work of two Rutgers professors – Julie Langsam and Stephen Westfall, who both teach at the Mason Gross School of the Arts – will be on display as at the Zimmerli Art Museum as part of the upcoming exhibition, Crossing Borders: Geometric Abstraction 1960 to Now.

The exhibition, which opens Sept. 11 and concludes July 31, will be featured in the Eisenberg Gallery at the art museum, 71 Hamilton St., New Brunswick, N.J. Admission is free.

“This exhibition is an exploration of abstraction across media, geography and time,” said Donna Gustafson, the Zimmerli’s chief curator. “Artists in the exhibition play with the language of abstract forms in landscape and urban scenes, music and dreaming states, and in two and three dimensions. Ultimately, the exhibition is a gathering of beauty in vivid color and in black and white.”

Gustafson added that Zimmerli officials hope this exhibition reminds viewers “that the basic principles of artmaking – whether that be a portrait, a landscape or a scene of everyday life – include a sophisticated language of abstract form. In our exhibition, this sophisticated language of abstraction is front and center.”

Langsam, whose art has been displayed in New York, Cleveland, Barcelona and Reykjavik, Iceland, is an associate professor of drawing in the Department of Art & Design at Mason Gross. A painter whose work spans filmmaking, photography and printmaking, Langsam was the former Joseph Motto Chair and head of painting at the Cleveland Institute of Art.

An abstract painter and art critic, Westfall is a professor of painting in the Art & Design department at Mason Gross and a Guggenheim fellow whose art has been shown in galleries and museums throughout the U.S. and Europe, including Boston, New York, San Francisco, Munich, Paris and Rome.

The two discuss their work and the Crossing Borders exhibition.

What is it about abstract art that keeps you continually interested?

Langsam: What I love about “abstraction” is that it is an abstract concept! What does “abstract” even mean? Does it mean that something is “abstracted from life” as in the work of Monet, Picasso, etc.? Does it mean that a form or shape is not lifelike? Does it mean that a form or shape or composition is arrived at in a different way than that of observing nature? Does it mean that the way something looks is different from what or how it accrues meaning?

I love abstraction because there are so many ways you can approach the concept. It makes the term slightly ambiguous, which enables a kind of slippage around the definition, and I am all for the embrace of the in-between spaces, the places where definitions are not set and new possibilities emerge.

Westfall: I find that abstract painting carries memories of pictures – figurative, architectural, landscape – without the burden of shifting ideologies.

I can even reference the binary compositional tensions in various "annunciations," such as the tug and lean between the angel and Mary, without the religious specifics. We all know those tensions.

What’s the thinking behind painting geometric and abstract shapes on top of your landscape photographs?

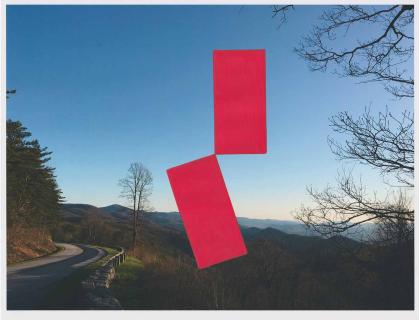

Langsam: I took these photographs while traveling across the Unites States for 5 months. Traversing over 30,000 miles across the country, it became clear to me that the landscape itself can tell the stories embedded within a place. Land – its uses and purposes, both historical and contemporary – can be seen as flashpoints for various ideologies and beliefs. Deeply rooted within the landscape are issues of sovereignty, agency, ownership and stewardship of land and natural resources.

The forms that I draw on top of the images – what I call “interventions” or “interferences” – are literally my own marks on the landscape, which I see as symbols or signifiers of the overwhelming legacy of our collective human impact on the environment.

Do you have any advice for Zimmerli visitors who are new to abstract art? What should they look for or at?

Langsam: I’ve always thought that while looking at a work of art one should focus on what they feel before they try to decode or understand what the artist’s motivations are.

For abstract works, looking at color, composition, form and material can all contribute to an overarching feeling or experience. Are the colors jarring or soothing? Are the shapes smooth and organic or angled and aggressive? Does the composition feel compressed or expansive?

Can you look at the image and not try to decipher it, but to just experience it and to sit with that experience for a while before the urge to understand what it means takes over? Try to stay in that place for as long as you can. Then when you find out more about the artist, the image, the motivation behind it, does your experience of the image change? How?

Westfall: Look at how abstract paintings are painted and imagine painting them yourself. Ask yourself what they remind you of in the exterior world. Notice how they address the space of the gallery.

What do you find so compelling about geometric forms?

Westfall: The rectangular format of a stretched canvas is already geometric, so there's already a built-in dialogue between interior and exterior shape in the picture. Geometric shapes can invoke bodies, architecture, rays of light and landscape. And they are ideal for presenting planes of color, or color as shape. The so-called "negative spaces" between geometric shapes are, of course, complex geometric shapes in themselves and endlessly surprising.

What’s one takeaway you hope museum guests walk away with after viewing your art?

Langsam: I would like the viewer to see the relationship of landscape to geometry; to see my geometries as literal relics of what we as humans leave behind. Ultimately, I would like viewers to reflect on how we interact/extract/impose and dis/respect our home – our planet.

Westfall: Only one? I'd like them to come away with a better understanding of how painting works and that they really could learn to do it themselves.