Three Professors Are Named Guggenheim Fellows

Rutgers-New Brunswick faculty Marc Handelman, Saurabh Jha and Miranda Lichtenstein are among 198 scholars and artists selected for the honor

A painter, an astronomer and a photographer – all professors at Rutgers University-New Brunswick – have been named to the 100th class of Guggenheim Fellows, which recognizes trailblazing artists and scholars and provides a stipend toward their work.

The three – Marc Handelman, Saurabh Jha and Miranda Lichtenstein – are among 198 fellows selected this year from a pool of nearly 3,500 across 53 disciplines, according to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, which recently announced the winners.

Established in 1925, the Guggenheim Foundation has granted more than $400 million in fellowships to more than 19,000 individuals, including more than 125 Nobel laureates, members of all the national academies, winners of the Pulitzer Prize, Fields Medal, Turing Award, Bancroft Prize, National Book Award and other internationally recognized honors.

Here are this year’s Guggenheim Fellows from Rutgers-New Brunswick:

Marc Handelman

Associate Professor

Department of Art & Design

Mason Gross School of the Arts

Field of Fine Arts

Marc Handelman, a painter who joined the Department of Art & Design at Mason Gross School of the Arts as an assistant professor in 2011, aims to blend elements of history, science and art into his latest work.

The Brooklyn resident will be focused on a project called Terra nullius that “involves making a long-term, multiyear series of paintings that reimagines the entire herbarium archive of botanical specimens collected during the Lewis and Clark expedition.”

“The work is about exploring and revisualizing these scientific documents to reflect on a critical moment in the making of the continental American empire, Manifest Destiny and Thomas Jefferson's engagement of Doctrine of Discovery Laws,” Handelman said. “In the paintings, I'm attempting to blur the disciplinary boundaries and genres between scientific archives, botanical illustration, landscape, history painting and abstraction.”

Handelman, who primarily works with oils but has expanded his repertoire to include walnut and sumi inks and watercolor, became an artist because “I think I've always just processed the world really visually.”

He added, “Making art became a language for expressing and communicating a lot of things that were otherwise inarticulate for me. And this was all deeply nurtured by my family. I feel so lucky for that support because the arts are an unconventional path.”

Right now, Handelman is working on his first feature-length video-animation.

You're communing with your artistic ancestors, and your artistic peers, you're trying to ask deeper and deeper questions about what this thing called art is ... what painting is, and what moves you in the world to make something.

Marc Handelman

painter

“Regardless of what media I'm working in, everything is connected to painting – to the social, and political and art-historical legacies of painting,” he said.

Handelman credited colleagues for being a source of both inspiration and encouragement.

“Beyond any awards or exhibitions, I just feel so grateful that I'm able to make my work and be in serious dialogue and fellowship with so many inspiring artists,” he said. “That includes colleagues and students at Rutgers to my artistic community in New York. The Guggenheim, and a bunch of other things I'm very proud of professionally, just wouldn't have been possible without the kind of creative engagement, dialogue and vision of all these people in my life.”

He added that making art and teaching art are closely related.

“You're communing with your artistic ancestors, and your artistic peers, you're trying to ask deeper and deeper questions about what this thing called art is ... what painting is, and what moves you in the world to make something,” he said. “Teaching and being an artist, they're both forms of learning, translation and exchange. And they’re both about world-making – in reimagining the possibilities of the world.”

As for being selected as a Guggenheim Fellow, Handelman said, “I'm really thrilled and humbled. And more than anything, at a time when so much research and so many ideas are being threatened, I'm so grateful for the opportunity and encouragement to move freely and deeply into this new work.”

– Mike Lucas

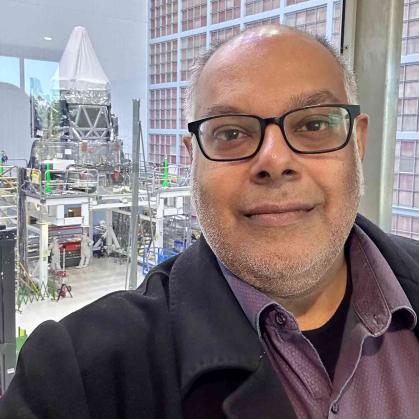

Saurabh W. Jha

Distinguished Professor

Department of Physics and Astronomy

School of Arts and Sciences

Field of Astronomy-Astrophysics

Saurabh Jha was a young teenager when the beauty of the universe first struck him.

The moment came one night during a family vacation in Arizona, when Jha sat in the back of the rental car as he, his parents and brother sped through the desert. As he stared out the window, taking in the utter darkness surrounding them, Jha spotted an unfamiliar glow in the heavens.

“I shouted, ‘Stop!’” said Jha of his first-ever glimpse of the Milky Way. “I made my family pull over on the side of the road, and we stood out there for an hour just looking.”

That instant of awe and curiosity crystallized a passion for astronomy, setting him on a path that would lead to groundbreaking discoveries about the universe. Decades later, Jha still is hunting objects in the sky, fulfilling a scientific quest to answer mysteries about particular kinds of exploding stars known as Type Ia Supernovae.

“I'm an observational astronomer, so I still get to look at the sky,” said Jha, who employs sophisticated instruments such as advanced telescopes, sky surveys, software tools and spectrographs that assess light patterns of celestial objects for tell-tale chemical constituents.

Jha has made significant contributions by focusing both on the astrophysical mechanism behind supernovae explosions and the application of using images of them to gauge distance in the universe.

For reasons that scientists don’t fully understand, Type Ia supernovae shine with nearly the same brightness wherever they explode in the universe, Jha said. Because of this, astronomers view each as a “standard candle,” using them to measure distances in space. This helps scientists map the universe and understand how it is expanding.

Jha said the Guggenheim Fellowship will enable him to write a review article on what kinds of white dwarf stars explode and how the explosion happens, focusing on what has been learned in the past decade, especially with new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope.

In my research, we’re looking at how the sky changes. We’re watching the movie of the universe. It's not a static thing. That's something that excites me.

Saurabh Jha

astronomer

Growing up in East Brunswick, N.J., Jha's interest in science was nurtured by a supportive family and inspiring teachers. Although his high school didn't offer astronomy courses, a physics teacher ignited his fascination with the physical world. This early interest led him to Harvard University, where he initially pursued physics but soon found his true calling in astronomy.

As a doctoral student at Harvard, Jha joined a team of astronomers working on a project that would change our understanding of the cosmos. Jha contributed by conducting measurements and observations.

In 1998, while studying supernovae, the team discovered that the universe's expansion was accelerating, a finding that contradicted previous expectations and introduced the concept of dark energy. This discovery marked a pivotal moment in astrophysics and earned two leaders of the team, along with the leader of a competing team that reached the same conclusions, the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2011.

After postdoctoral appointments at the University of California, Berkeley and Stanford University’s Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, Jha joined the Rutgers faculty in 2007.

Jha’s fascination with supernovae and his involvement with the discovery of accelerating expansion have inevitably led him to also investigate dark energy, a mysterious force that counteracts gravity and accelerates the universe’s expansion.

“We call it ‘dark energy,’ but we don't know what it is,” Jha said.

By observing more supernovae at different times in the universe's history, Jha and other astronomers have measured the expansion rate more precisely. This has contributed to a better understanding of the nature of dark energy and how it may influence the universe's expansion.

“In my research, we’re looking at how the sky changes,” Jha said. “We’re watching the movie of the universe. It's not a static thing. That's something that excites me.”

– Kitta MacPherson

Miranda Lichtenstein

Associate Professor

Department of Art & Design

Mason Gross School of the Arts

Field of Photography

Miranda Lichtenstein’s recent photography relies as much upon the printer as the camera.

“I run the paper through the printer many, many, many times,” she said, “layering image over image” until the layers of ink create tone and depth that sit both in and on the surface.

Her next major project, using her Guggenheim Fellowship to photograph recently discovered frescos in the ruined Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, likely will add another layer of information: hidden pigments detected by special cameras that see wavelengths humans cannot.

Born in New York and raised near Boston, Lichtenstein discovered photography through her brother, a photojournalist who built a darkroom in their home when he was 14 and she was 11.

At Sarah Lawrence College, she studied under Joel Sternfeld, so “straight photography” was the dominant paradigm, but she felt lucky to see work by women in the early 1990s who had a dramatic impact on her.

“Joel was a compelling mentor, even though his style was not mine,” she said. “I was able to healthily work against him.”

At age 19, she cold-called the artist Nancy Spero after looking her number up in the phone book and landed an internship that exposed her to the Pictures Generation during her visits to galleries near the studio – artists such as Sarah Charlesworth, Louise Lawler and Cindy Sherman who were "looking at culture and media and thinking about appropriation as a subject as well as a material."

I’m interested in what happens when the technology does something it wasn’t supposed to.

Miranda Lichtenstein

photographer

To pay rent after graduate school at the California Institute of the Arts, she worked as an assistant photo editor at Interview and then as a photo researcher at Vogue. The Vogue gig, which occupied her just two weeks a month, left two weeks for the studio and funded residencies from Giverny, France, to upstate New York.

Teaching arrived almost by accident. Lichtenstein started with a single class at Cooper Union, then a sabbatical replacement for Sternfeld and finally, in 2011, a post at Rutgers where conversation with students keeps the questions fresh.

“If you don’t have any questions, there’s not much to rely on in the studio,” she said.

The questions now revolve around how many images a single photograph can hold. Lichtenstein keeps an iPhone library tagged by motif – circles, yellow, glass – and layers those shots to build what she calls “non-objective” pictures that hover between camera and canvas. Although she finds artificial intelligence’s threat to conventional photography troubling, she embraces other technology, like the scanners she will use in Italy.

She plans to study freshly uncovered frescoes, record them with a handheld light detection and ranging (LiDAR) device and feed the data into her image-making software. The finished work, destined first for a book, won’t illustrate archaeology so much as converse with it. Lichtenstein wants the surface to feel unstable and time-lapsed.

“I’m interested in what happens when the technology does something it wasn’t supposed to,” she said of her plans to make art from LiDAR.

“I'm interested in frescoes, in part because I'm interested in how they're made,” Lichtenstein added. “They're done very quickly on the limestone. I'm curious about how I can look at them and rethink substrates for my own work.”

– Andrew Smith