Nine on Title IX

An Amendment That Changed History

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972

"No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

50 Years Later

Half a century after this groundbreaking gender-equity legislation was signed into law, nine informed voices from Rutgers’ esteemed faculty offer their own reflections and unique perspectives on its far-reaching effects across these various topics:

"The legislative history of Title IX set forth the links between gendered discrimination in education and access to better employment opportunities"

- Tamara Lee, Assistant Professor, Labor Studies and Employment Relations

Acknowledging the importance of education as a gateway to social mobility, sex-based discrimination in the educational realm was framed as an obstacle to equitable labor market participation and financial security as well as the perpetuator of economic violence against women relegating them to second-class citizenship.

The passage of Title IX in tandem with the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade ushered in an era of bodily autonomy that sits at the foundation of gains in gender equity attributable to and within the field of education. Five decades later, any achievements in sex-based equity are in peril as an increasing number of states pass trans-exclusionary laws and anti-abortion statutes that carry implicit and explicit labor and employment consequences.

While new Title IX rules from President Joe Biden’s Department of Education seek to more clearly bring sexual orientation, gender identity and transgender status under the umbrella of federal antidiscrimination regulations, The U.S. Supreme Court appears poised to undue long-standing rights of women and birthing people to make decisions about their bodies that have long increased their educational attainment and workforce participation. That is to say the current juridical, administrative and legislative focus at all levels on the scope of “sex discrimination” as it pertains to gender, gender identity and sexual orientation raises the stakes on equal protection and the rights to privacy for women, nonbinary and trans students and educational workers.

For a nation fully ensconced in intersectional culture wars being fought at the situs of our educational institutions, those words, and the interpretation of them, have never been more relevant and vital to workplace democracy and democracy at large.

“Rep. Patsy Takemoto Mink of Hawaii once told a reporter, ‘I didn’t start off wanting to be in politics. I wanted to be a learned professional, serving the community. But they weren’t hiring women just then. Not being able to get a job from anybody changed things.’”

- Jean Sinzdak, Associate Director, Center for American Women and Politics

When Title IX passed in 1972, Mink, the legislation’s first author, was one of 13 women serving in the 535 seats in the U.S. Congress. She also was the first Asian American woman and the first woman of color elected to Congress.

Mink’s trailblazing service in the House came after a number of professional obstacles had been thrown her way. Despite a stellar academic record, she was rejected from numerous medical schools, some of which point-blank told her that they did not accept women. Eventually completing law school, she struggled to find a job. Many firms simply would not hire women. These experiences of overt discrimination inspired her to spearhead Title IX to prevent others from being subjected to similar treatment.

In the 50 years since Title IX passed, millions of women have attended colleges and universities previously closed to them. Women also have closed the enrollment gap in medical and law schools. If you ask a roomful of young women how many of them have been involved in sports, a majority are likely to raise their hands, a direct result of opportunities opened by Title IX.

But one of Title IX’s most lasting impacts is that it heralded an era in which women began to come into political leadership and wield their political power. Today, a record 145 women serve in Congress, including a record number of women of color. Title IX did more than open up higher education and athletics for women: It also showcased the power of women’s leadership to make a difference for gender equity. It’s fitting that Title IX was later renamed the Patsy T. Mink Equal Opportunity in Education Act, a powerful symbol that representation matters.

“Title IX protects individuals in educational programs from any sex-based discrimination. This protection extends to women and LGBTQ+ individuals.”

- Perry N. Halkitis, Dean and Professor Director, CHIBPS, Department of Urban-Global Public Health, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology

Title IX protects individuals in educational programs from any sex-based discrimination. This protection extends to women and LGBTQ+ individuals.

In this field of public health, women and sexual and gender minority individuals lead local, national and international governmental organizations, schools, nonprofits and much more. In many ways, public health is ahead of other fields such as medicine in its advancement of women and sexual and gender minorities as well as in upholding protections for gender, gender identity, and sexual identity. As the lead author of the Zero Tolerance Statement For Harassment And Discrimination Adopted By The Association of Schools and Programs of Public Health (ASPPH), I am confident this ethos exists in other school and programs of public health throughout the U.S.

Unfortunately, this all happens within the context of a nation that is chipping away at the rights of women as well as sexual and gender minority individuals. It also is in the context of a nation in which the U.S. women’s soccer team had to sue for equal pay, where transathletes are being shunned by universities and essentially ignored by the NCAA, and where laws are being enacted such as the one in Florida that prevents an open dialogue about sexual and gender identity in schools.

While public health will continue to advance the prominent role that individuals who identify in one of these multiple ways, we do so with full knowledge the battle rages on with regard to the passing of legislation that does nothing more than undermine the health of women as well as sexual and gender minorities in the U.S. Public health stands up front in fighting against these forms of discrimination and against the all forms of racism that are intimately intertwined with misogyny, homophobia and transphobia in all sectors of society—including higher education.

"While I was an undergraduate and then a medical student, I found it always baffling that women were depicted as the ‘weaker sex,’ because of their monthly menses and pregnancy.”

- Gloria Bachmann, Associate Dean of Women's Health, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

While I was an undergraduate and then a medical student, I found it always baffling that women were depicted as the “weaker sex,” because of their monthly menses and pregnancy. Even the issue of women not being able to withstand the rigors of physician training, including obstetrics and gynecology training, was prevalent in the past before Title IX. I was one of the fortunate women to have as a medical school teacher and role model Dr. Helen Dickens, who herself was a trailblazing Black obstetrician and gynecologist as well as a health-equity advocate and social activist. She herself was the first Black woman to be admitted to the American College of Surgeons.

I was mentored by Dr. Dickens at a point in my training when I was deciding which specialty path to take in medicine. Dr. Dickens, by her example, taught me (as well as all the women she mentored) to follow your dream, your vision—and that being a female should never be a deterrent. That is why I pursued obstetrics and gynecology at a time when most of these clinicians were men.

Staying at the University of Pennsylvania for my residency gave me more opportunities to be mentored by Dr. Dickens. It was through her example in clinical settings, in the operating room and during hospital rounds that I got to further learn from a woman health-care leader. Her example also is the reason why I pursued academic medicine.

Like Dr. Dickens, I too want to make a difference. I too want to be a mentor and role model like Dr. Dickens to the next generations of the healthcare team. That regardless of your gender, that regardless of who you chose to love, that regardless of your background, you follow your dream, your vision.

There are no words that can adequately describe my gratitude toward Dr. Dickens. I know that she was one of the many voices who helped Title IX become a reality.

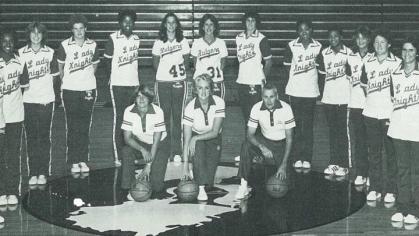

“As a former collegiate athlete, I experienced both the benefits and disparities of Title IX.”

- Kiamsha Bynes, Doctoral Student, Department of History, School of Arts and Science

I obtained a full scholarship that granted me access to higher education. As a Black woman who played basketball, I was a part of the majority, where more than half of the NCAA women's basketball players looked like me. Contrarily, the racial makeup of head coaches and athletic administration placed Black women on the sidelines in the minority, thus demonstrating how the impact of Title IX for Black women has been twofold, in some cases exceeding and in others lacking.

Before Title IX, a vast majority of Black sportswomen attended historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs). While some argue the rise of Title IX fostered the demise of HBCU athletic programs, it is essential to see how it opened the door for Black women to compete, attend and eventually coach at high major programs outside of Black institutions. The 2022 NCAA Basketball Tournament featured 12 Black female head coaches, displaying a historic representation of Black women in the sport. But there is certainly more room to grow. Of all the Power Five conferences, the Big Ten lacked most, as Rutgers’ very own C. Vivian Stringer remained the only Black woman head basketball coach up until this year.

Fifty years after the passing of Title IX, it is undeniable that the realm of sport has seen the biggest increase in women’s participation. Although not perfect and far from balanced, Title IX has provided a foundation for Black women to enter sporting positions at the collegiate level. In years to come, I am hopeful the influence of Title IX will create more diversity not only in coaching positions, but in sports like tennis, swimming, and soccer where Black women do not make up the majority.

At Rutgers, individuals can find the opportunity and support they need to excel. Today, as the ripples of Title IX continue to uplift new generations, we continue strive to be a place where all individuals have a voice. In that spirit, here are nine key moments that demonstrate our commitment to diversity, inclusion, and representation.

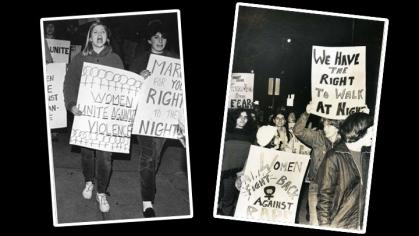

“Title IX bans sex discrimination in federally funded education programs and therefore includes essential protections from sexual violence and harassment.”

- Sarah McMahon, Associate Professor and Director, Center for Research on Ending Violence, School of Social Work

Although we are celebrating the 50th anniversary of Title IX, it wasn’t until the past decade that higher education’s role in preventing and responding to sexual violence and harassment under Title IX were clarified.

This happened in part because student activists throughout the nation mobilized to share how colleges and universities had mishandled their complaints of sexual misconduct and to call for change. President Barack Obama's administration prioritized these issues. In 2011, the Office of Civil Rights issued landmark guidance to broaden the role of higher education institutions in addressing sexual violence on and off campus.

This allowed students to use civil action to hold higher education accountable under Title IX for how they handle sexual misconduct. This fueled many positive changes at colleges and universities across the country, including here at Rutgers. Students have helped develop innovative policies, procedures, and programs to respond to and prevent sexual misconduct.

Guidance on using Title IX to address sexual violence and harassment continues to change, based on federal administration, and student activists continue to play an essential role in its interpretation. Although much has been accomplished, there is still much work needed to ensure that our campuses are safe and welcoming for all members of our community.

Sexual assault and sexual harassment are widespread and insidious issues on college campuses. Although these acts affect people of all genders, women and nonbinary students are disproportionately impacted. Title IX bans sex discrimination in federally funded education programs and therefore includes essential protections from sexual violence and harassment.

“Clearly, it was time to stop defending the indefensible. Title IX meant that admissions were no longer unequal.”

- Lisa Klein, Distinguished Professor and Department Chair, Materials Science and Engineering

When Title IX was enacted in 1972, I was beginning my senior year at a university that was primarily an engineering school. Women students were less than 5% of the student body. We were told that the number of women students was restricted because there was only one dormitory, and once all of the beds were filled, it was not possible to admit any more. As a result, women students on average had higher GPAs and SAT scores than men.

Once co-ed dorms were introduced, that argument was harder to make. Instead, we were told that admitting more women would change the distribution of majors. Women would choose life sciences instead of electrical engineering, and there would be a mismatch of faculty and student enrollments. That prediction did not come to pass when larger numbers of women were admitted. Clearly, it was time to stop defending the indefensible. Title IX meant that admissions were no longer unequal.

I celebrated when I heard about the passage of Title IX because it meant that women were no longer invisible. Clearly sports was not the main driver because we had no athletic scholarships. Our issues stemmed from attitudes like, “Girls can’t be engineers because they don’t change the oil in their car themselves.” Let’s face it, there were many attitudes and practices that preceded Title IX that Title IX did not address. Nevertheless, it did come at the right time, prompting university administrators to stop and think about how they made decisions.

Was it because it was the way things had always been done, or was it in the university's best interest moving forward? I like to think that Title IX started some soul-searching that improved the outlook for everyone.

“The landmark gender-equity law, Title IX, helped remove the barriers women faced in health care and other fields so I could become an oral and maxillofacial surgeon.”

- Pamela Alberto, Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Rutgers School of Dental Medicine

It allowed me to attend an engineering college that had few female students. I was even able to play in a male intramural ice hockey league in college. It then allowed me to attend a dental school with the largest number of women at that time. However, in dental school, there were few female role models to be found: My school had only one female faculty member.

When I decided to specialize and become an oral and maxillofacial surgeon, the department chairman met with me to tell me why women don’t belong in the profession. He had convinced me I would never be accepted to a program, so much so that I had decided not to apply. But my husband convinced me to try. During my interviews, most program directors spent the whole session explaining why women don’t belong in oral and maxillofacial surgery. But Title IX forced residency programs to interview and accept women, and I felt fortunate to be accepted. Thanks to Title IX, I became the second woman oral and maxillofacial surgeon in New Jersey. Today, 19 percent of surgeons in this field are women. There’s still work to be done, but we continue to progress toward equity.

“‘You don’t look like a CFO,’ the venture capitalist told me as I walked him through our company's valuation during a funding round.”

- Lisa S. Kaplowitz, Assistant Professor, Finance and Executive Director, Rutgers Center for Women in Business

Shortly after I committed to Brown University as a student-athlete on the women’s gymnastics team, they cut our team. I was the last recruited gymnast, and turned down full rides at other universities. This was crushing. As a last resort, my teammates and two volleyball players sued our school under Title IX. The hours I wasn’t studying, training, or working to pay for college were spent testifying in court and helping our lawyers prepare for the case. In 1998, after six years, appeals up to the Supreme Court, and nearly $3 million of litigation in which Brown unsuccessfully claimed budget cuts forced the elimination of these two women’s teams with a combined budget of $62,000, the university finally settled. Brown added more women’s teams.

Title IX not only gave me the opportunity to play sports, it helped me find my voice and feel confident throughout my professional career in the male-dominated finance industry. When I started my first job, I was one of two women in my investment banking analyst class of 20, and the only woman in my industry group who wasn’t an administrative assistant. My Title IX experience also kickstarted the advocacy that I would continue throughout my career in finance and in academia, where I co-founded the Rutgers Center for Women in Business to remove barriers, build community, and empower women.

Fifty years ago, Title IX was passed as part of the educational amendments of 1972 to ensure women had equal opportunities to participate in all education programs or activities which received federal funding. Thirty years ago, my college teammates and I signed on to what would become a landmark Title IX case, setting a precedent nationwide for more colleges and universities to add opportunities for women to play sports. At the time, we didn’t appreciate the impact this case would have on women athletes and, ultimately, ourselves.